Econometrics as a solution to blind spots in your marketing strategy: Grizzlink introduces econometric analysis.

Econometrics as a solution to blind spots in your marketing strategy: Grizzlink introduces econometric analysis.

You have the efficiency of your digital channels sorted thanks to ROI or ROAS, but can’t evaluate the impact of other channels offline? And how to analyse situations where the customers decide to buy your product based on your TV and through Google Ads only finishes the purchase? Based on the ROI in Google Analytics, the impactful channel is Google Ads and TV remains attributeless. Had it not been for it, though, the purchase would’ve never happened. How to approach this?

Grizzlink introduces a product among its analytical services which resolves all these pickles and helps brands make more informed strategic decisions: an econometric analysis.

Up until now, econometrics was mainly the domain of large corporations with deep pockets. Grizzlink strives to level the uneven playing field between David and Goliath and brings this tool not only to large media spenders but also to medium-sized companies whose strategic decisions have been clouded by intelligence blind spots. As with anything in marketing, the econometric analysis should be perceived as an investment, not an expense. Investment improves strategic decision making and strengthens your competitiveness in the long term.

Econometrics?

Econometrics is a field that explains economic relations through the use of economics, mathematics and statistics. It works with datasets worth of historical data, independent and dependent variables. The independent variables include media mix impressions (both you and your competitors), macroeconomic indicators, and other relevant factors; all on the weekly basis. The dependent variable is then business results – most frequently sales, but also a number of leads, store visits etc. To put it simply – the fundamental outcomes of an econometric analysis are the interpretation of the past, streamlining the present and predicting the future. Too ambitious? Read further.

1. Interpretation of the past

Thanks to the analysis of historical activities, we can evaluate which individual channel had the most impact on sales. Without thorough econometric analysis, it is virtually impossible to determine which channels are impactful and to what extent. At the same time, we can detect which channels are simply dead weight ready to be cut out off the media mix. The essential difference between an econometric analysis and an advanced attribution model is that the former does not examine a path to purchase of an individual customer, but works with the whole customer base.

What’s more, we don’t have to limit ourselves to media mix, but we can analyse other factors such as a creative, economic situation or cultural trends. This brings us to the next use of econometric analysis: making the present more effective.

2. More effective present

People best learn from their own mistakes, right? These don’t necessarily have to be mistakes. You could do all the planning by the book but thanks to econometrics you still find out that there is a slightly better split of media for your specific target segment. This way, econometric analysis can save up to 20% of your planned budget and redistribute it for improved effectiveness. Thanks to econometrics the next term will be planned based on real data specific to your segment and your brand. You don’t have to rely on assumptions or best practices for planning anymore.

3. Predicting the future

Thanks to econometrics, you can also predict your key performance indicators based on a specific media mix. Find out what the impact will be if you reallocate 10 % of your media spend to TV campaigns. What the consequences of halting your consumer contests will be. Simultaneously, you will be able to predict the impact of forces outside of your influence which still can have an impact on your business, such as macroeconomic indicators, cultural trends or the impact of weather.

It is noteworthy, however, that all these predictions must be based on historical activities. Although you can foretell the sales volume if you reallocate 10 % of your budget from one channel to another, you cannot predict the impact of adding a new channel, which you haven’t used before.

Case study

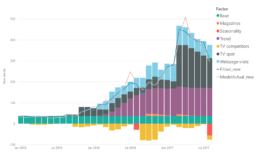

Analysis description

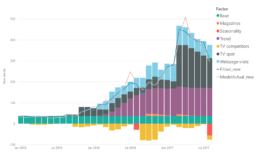

- The following case study is an analysis of an anonymous brand within the financial sector. We examine two financial products separately, but also within their mutual relationship across three and a half years with weekly data.

- The goal of the analysis was to determine the factors influencing the acquisition of new clients and to define future managerial recommendations.

- Entry data

- No. of new clients

- Media mix, both the brand’s and its competitors’

- Interest rates, own and the market’s average

- Webpage visits

- Seasonal factors

Main insights

- Media effectiveness: the crucial factors for Product 1 sales are TV campaigns and web visits. As for Product 2, besides TV and web, print ads also contribute to sales.

- Customer journey: TV serves as the first point of contact, builds brand awareness and influences website visits.

- Selection of media: the recommended approach for TV campaigns is to invest GRP between 200-250 for Product 1, and between 400-450 for Product 2.

- ROPO Effect: 1 out of 4 customers looks up Product 1 online, but purchases offline. For Product 2, on the other hand, ¾ of new customers search online and finish purchases in the branch office.

- Spillover effect: the TV campaigns for Product 1 have a positive influence on the number of new customers for Product 2.

- Base line (acquisition of new customers irrespective of marketing activities): Product 2 sees an increasing baseline thanks to long-term TV campaigns. Despite the basic hypothesis, this trend is not apparent for Product 1.

- TV campaigns contribute to webpage visits in 38 % of all cases. Webpage visits contribute to the acquisition of new clients in 63,7 % of cases.

- Carry-over effect (the impact of ads in one month on the customer behaviour in the following month) is at 20 %.

- Optimal Gross Rating Point is between 200 and 250 GRP.

- Increase in the baseline due to TV campaigns has not been detected yet despite the hypothesis built on the strength of TV campaigns.

- Webpage visits contribute to the ROPO effect (searching online, buying offline) in 28,4 % of cases.

- Only competitors’ TV campaigns have a negative influence on the acquisition of new clients.

- Competitors’ communication takes up 46,4 % of potential new clients.

- The number of new clients is affected by TV campaigns, website visits and print ads.

- The TV campaigns for Product 1 have a positive effect on the number of new clients for Product 2 (+67 new clients = 1,5 %).

- Long-term campaigns affect the increasing baseline.

- Long carry-over effect for Product 2 enables longer periods between campaigns (2-3 weeks).

- Ideal Gross Rating Points is between 400 and 450 GRP.

- ROPO Effect is at 78 % – approximately 3 out of 4 new customers search for information online and purchase in the branch store.

- TV campaigns contribute to webpage visits in 38 % of all cases. Webpage visits contribute to the acquisition of new clients in 63,7 % of cases.

- Carry-over effect (the impact of ads in one month on the customer behaviour in the following month) is at 20 %.

- Optimal Gross Rating Point is between 200 and 250 GRP.

- Increase in the baseline due to TV campaigns has not been detected yet despite the hypothesis built on the strength of TV campaigns.

- Webpage visits contribute to the ROPO effect (searching online, buying offline) in 28,4 % of cases.

- Only competitors’ TV campaigns have a negative influence on the acquisition of new clients.

- Competitors’ communication takes up 46,4 % of potential new clients.

- The number of new clients is affected by TV campaigns, website visits and print ads.

- The TV campaigns for Product 1 have a positive effect on the number of new clients for Product 2 (+67 new clients = 1,5 %).

- Long-term campaigns affect the increasing baseline.

- Long carry-over effect for Product 2 enables longer periods between campaigns (2-3 weeks).

- Ideal Gross Rating Points is between 400 and 450 GRP.

- ROPO Effect is at 78 % – approximately 3 out of 4 new customers search for information online and purchase in the branch store.

Stereotypes in marketing

At the center of any marketing communication there must always stand the customers. However, despite technological advances, we still cannot collect all the data about them. This is why we often make our work easier with a number of projections designed to help us refine our targeting. But we must treat them with caution and verify whether we are not just subject to socially deep-rooted stereotypes in our conclusions.

A good example of stereotyping, for example, is the player of computer games. Many imagine a younger man who spends the whole day at the computer and practically doesn't talk to anyone. Therefore, it can come as a surprise that the statistical representation of men and women among global players is perfectly balanced (year-on-year deviation of +/- 2 %), and with one quarter, we are talking about a persons aged 45 years and older.

It concludes that a stereotypical assumption does not equal statistical data.

Multinational FMCG company Unilever decided to set an example in breaking stereotypes in advertising . Their corporate marketing communication tries to follow social developments and so break the traditional roles and social portraits, which belongs perhaps to the last century, and today, they cannot be arbitrarily applied on consumer behaviour. Already in 2017, they founded an association that connects other organizations, and they all work together to eradicate stereotypes in all advertising formats.

In the video below, you can watch their DNA experiment.

Presenting the two most common stereotypes that interfere with segmentation, now.

Age matters (not)

We often apply a common stereotype in dividing and comparing generations to each other. We attribute to them uniform patterns of behaviour and define their consumer decision-making only on the year of birth basis. We call them inappropriately segments and pair them to one medium, which this or that generation uses most often – for instance, the Digital First approach for Generation Y or Social First approach for Generation Z. However, the generation does not resemble a definition of any segment, by far. You can just look around yourself, how behave those of same age, our peers, and we can notice a surprising thing – our age says nothing about our interests or how we spend our work and leisure time.

Take, for example, millennials. Every once in a while, a study that analyses Generation Y behaviour comes out, but the results don't support what is widely claimed. The behaviour and decision-making of millennials doesn't make a significant difference to previous generations. It is just younger and maybe a little poorer till certain age. Therefore, marketing should perceive age only as a number, that itself says nothing tell, and don't fixate on presumptions. It is the behaviour of each individual itself that should interest us.

Another widespread stereotype then applies to traditional media. We often see them as retreating, with younger generations spending their time on phones alone. Again, statistics say something else. Though, one cannot of course deny that, today, we spend more time on-line than ever before, to underestimate the reach of traditional media would also be a costly mistake. Instead of looking for the most relevant media, we should rather decide in what proportion a suitable mediamix will be compiled.

Mr Blue and Mrs Pink

With the problem of the for some outdated perception of gender roles of men and women today, we still encounter almost everywhere, although the topic itself is not that new. The ways in which these stereotypical roles are reflected in marketing are increasingly causing the opportunity to reach potentially more profitable customers to be missed. Research by the British research agency Kantar suggests that two thirds of women think current ads negatively portray the role of a woman.

Whether we're talking about a social role, or the ways the product is communicated, marketing often overrates whether a customer for a product should be woman or man. Still, in advertising there apply old standards, that the man is the head of the family, at the same time, the technical type, and clueless in the household, while women on the contrary, belong to the house-keeping and in their spare time they buy things they don't need. But that certainly this cannot be applied nowadays, so brands possible forgetting some of their potential customers is based solely on these unfounded assumptions.

But gender stereotypes by far don't concern adults only. Gender marketing among children's toys may be an even bigger problem than among adult products. Division of products in pink and blue or cars for boys and dolls for girls today is a complete standard, which has surpassed the period before 50 years ago, which was generally on far more discriminatory in social norms. Even despite the fact, that according to research, the girls today equally with the boys show interest in the video games and quarter of them won't wear anything pink. For example, the worldwide popular brand Lego decided to test its products by a mixed group, only a few years ago. In doing so, it is clear that such a decision may have previously had a major impact on prototyping products and expanding the portfolio of small customers.

In the year 2018, the British Advertising Standards Authority (ASA) came with the new set of rules, which should the British advertising industry follow in order to eliminate, as much as possible, the negative impact of advertising on the perception of male and female roles in society. But it was rather a first try to point out the fact that old order no longer fits today, and may generally have a negative impact on society.

How do brands try to work with breaking of stereotypes?

In 2019, globally popular sub-brand Diet Coke set out into the world with the campaign Unlabeled – Imagine the World Without Imposed Labels, that tried to tear down stereotypes built around gender roles, ethnic groups or sexuality. It was also a message that not every "label" is bad, it just needs to get to know to the individual more in depth.

In recent days, there has been a wave of reactions in recent triggered by spot of Girls. Girls. Girls magazine "Don't be a Slut. Be a Lady they Said" that shows gender labels and stereotypes associated with the role of a woman in society.

Thus, it tries to provoke a discussion over the absurd demands that are burdened on women, and the impact on their self-esteem. Also the Dove brand has been successfully fighting with this in its ads, for a long time.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=1&v=7rM6BOdqORE&feature=emb_logo

How to avoid the mistaken stereotypes?

The difference between targeting a stereotype, and a real group of potential customers is only in data and research implementation. Better prevention of inaccurate segmentation does not exist. As we have showed on several examples, statistics often go in an unexpected direction compared to what we read or hear.

When marketing is a cost centre

Or how the marketers became paper salesmen and the key competences on the company direction took over their colleagues from other disciplines.

It happens to the more experienced, too, that we let ourselves manoeuvre into the situation in which we talk about a marketing budget long before it can be defined how much our funny colleagues-marketers contribute to our business target. It originates from the times not long gone when some marketers could dream as they liked, as they had a very little say in key decision making, and every penny, they wished to use to prepare a dinner for key customers, photo shoot or PPC campaign, had to lengthily argue over with the real management.

Transition to zero-based budgeting is stressing, in any case. To wake up one day to find out there isn’t a penny for marketing available. No allocated budget with comfortable cushion for four decent campaign and few small ones. Along with a continual budget for social networks, PPC, graphics, copyrights, CMS, radio and something for smaller productions. And suddenly not a penny more. At least, one can only blame themselves. Finally, to take the plunge and make a long postponed resolution lying in one’s head come true. Also to smash this idea of some colleagues that the company could thrive and grow, even if there were no Facebook, Instagram, Adwords or YouTube.

And outright count with the fact that like all ambitious plans, not all can be done in time, originally dedicated to it. You know, to get the key people from all departments together at company parties and what more, to provoke a little bit of activity in them is no fun. It will happen, after all, in days or more likely in weeks later. By that time, not only a larger part of company roughly knows, but also believes that the marketing has actually quite crucial relevance for company’s functioning. Still, a primary goal is something slightly different. The primary goal is start investing money into the marketing, not spending. In short, to know very well which marketing activity contributes to the business targets which originate from the company’s get-togethers. To plan campaigns with a clear awareness of what leads where and what sense it makes. To define not just in outlines, but with full knowledge of what marketing activity can help the brand metrics, how these brand metrics will in a long-term plan transform into the business results. To establish, along with this all, what marketing channels one uses and what value for money ratio one achieves.

Everyone somewhat guesses how did we get to beforehand planned marketing budgets, back then. Like with many other things, it all comes to the mental laziness, comfiness and laziness, again. To change things, you know, when they work has been always tricky. On the other hand, this is the way how the marketing department becomes a cost centre in the eyes of people from other departments. A centre that delivers on average, consuming resources above average.

And even if we wouldn't mind it for some time, we would find it a little bit sad if we suddenly found ourselves being unwanted, quietly tolerated and sadly insignificant.

So hit it hard and perhaps you’ll find out that the zero-based budget can result in even bigger budget!

Marketing ≠ communication

Everybody knows marketing communication. However, do we really have to consider it as the only important part of marketing?

What marketing is and is not.

Great deal of us read some marketing definitions at college or university and then passed respective exams. These marketing theory definitions have been with us for more than fifty years, so we will remind you of them.

According to the American Marketing Association, marketing is the activity, set of institutions, and processes for creating, communicating, delivering, and exchanging offerings that have value for customers, clients, partners, and society at large.

Keisha M. Cutright, Assistant Professor of Marketing at The Wharton School in Pennsylvania, USA, says that we can consider marketing as an independent organisational unit or as a set of processes focused on understanding the customers and meeting their needs.

Among these issues, there belongs often a decision about what products to make, where to sell them, how to promote them and what are their prices.

Although these principals are more than fifty years old, as mentioned above, nothing about them has changed still. It is not primarily about the product, as many think, it is about the customers and their needs.

That is why we need to realise one thing, closely related, that marketing ≠ communication.

What is communication?

Communication cannot be described simply as an advertisement (ATL, BTL), digital, PR, events and much more. It is a vital part of marketing, the most visible one, but it is still only its part. The communication itself is preceded by a lot of important work that matters in practice the most.

Why is it wrong?

Our little marketing pool mostly tries to figure out what campaign it is doing with no worked out segmentation, knowing nothing about the customers’s motives, not thinking about the product itself, its price, and without a proper strategy to roof it all up for a period longer than the actual three month campaign. Unfortunately, then it happens that the campaign is nice, but useless. Business either stagnates or even goes down. The market share doesn’t move or we even plummet. As we don’t execute surveys, we don’t know if the brand awareness is going up or down, not to mention other useful metrics. And one of the reasons is our approach when we do only communication.

Is it because of the fact that other parts of marketing are boring, or they are not seen, and then we have nothing to boast about at the conferences? Or there is a large number of agencies and they make their clients simply do? Or the Czech marketers don’t have such know-how and have now idea how to work with marketing?

The reasons will be countless, which we can study indefinitely, or we can inspire ourselves by successful approaches, proven in practice and yielding results. Mark Ritson promotes one such interesting approach.

What does such strategy looks like?

Mark Ritson is a professor Adjunct Professor of Marketing at Melbourne Business School, a marketer, who has experience with working for the biggest brands (LVMH, GSK, Pepsico etc.).

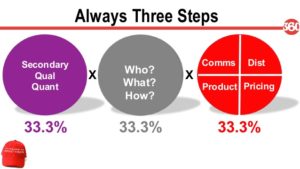

Last but not least, he is an excellent speaker who can get attention even from the biggest sleepers of marketing events through his presentations and appearances. To simplify, we can describe this marketing approach in three steps. Analysis, strategy, tactics.

Analysis

The basis is understanding the market and creation of segmentation. Segmentation is not targeting. Segmentation has nothing to do with brand or society. Segmentation can be described as an objective classification of target audiences in the market. Interesting enough, if the competition has the same target audience and does it all right, the same segmentation is achieved. At this stage, we have to find out too, what the customers think. We begin with quantitative research, and the acquired data then verify with qualitative research. Let’s forget what we marketers think and let us listen to the customers.

Strategy

The magical word “strategy” is to mainly define what we will and we will not do over next twelve months. How we will aim based on each segment (typical mistake is - we aim at all). We must set narrow but distinct positioning within the market, coming from where we will stand firm or where not, and what is our goal to represent to the consumer. Lastly, we set clear, measurable, strategic goals for a period not longer than twelve months. At the same time, we can use three simple questions - Who? What? How?

Tactics

Final part of marketing concerns the product development, price formation, distribution and then our favourite discipline - communication. Here we must add, mathematically the communication is only eight percent of marketing. On the top of that, at the end of the whole process. Every area is clearly defined and builds on previous steps. Practically, we can say we still do marketing without communication, and it even delivers. The most important about it is that if we mess up step one or two, we do such communication in vain, as it won’t simply work.

Conclusion

This approach is not an easy one, it requires much work, much persuasion, be it the colleagues, superiors and many other people from the industry who will stubbornly claim that communication = marketing. Let us use follow the principals defined decades ago and are constant. Everything is about the customer, their motives and the ways how to meet their need.